Whale monologues

A North Atlantic earthquake

Sea creatures from the Midnight Zone. Puzzle 1.

Deep-sea biology was not on our mind when setting sail on our expedition. But as we were getting our seismometers back up from the seafloor, we found a variety of living creatures on them.

In effect, we have performed a fairly large-scale growth experiment. It went like this: put metal-and-plastic structures on the seafloor at 1-4 km depths; let in place for 19 months; retrieve and examine what grew on them; repeat over a vast area with a range of seafloor depths and geological settings.

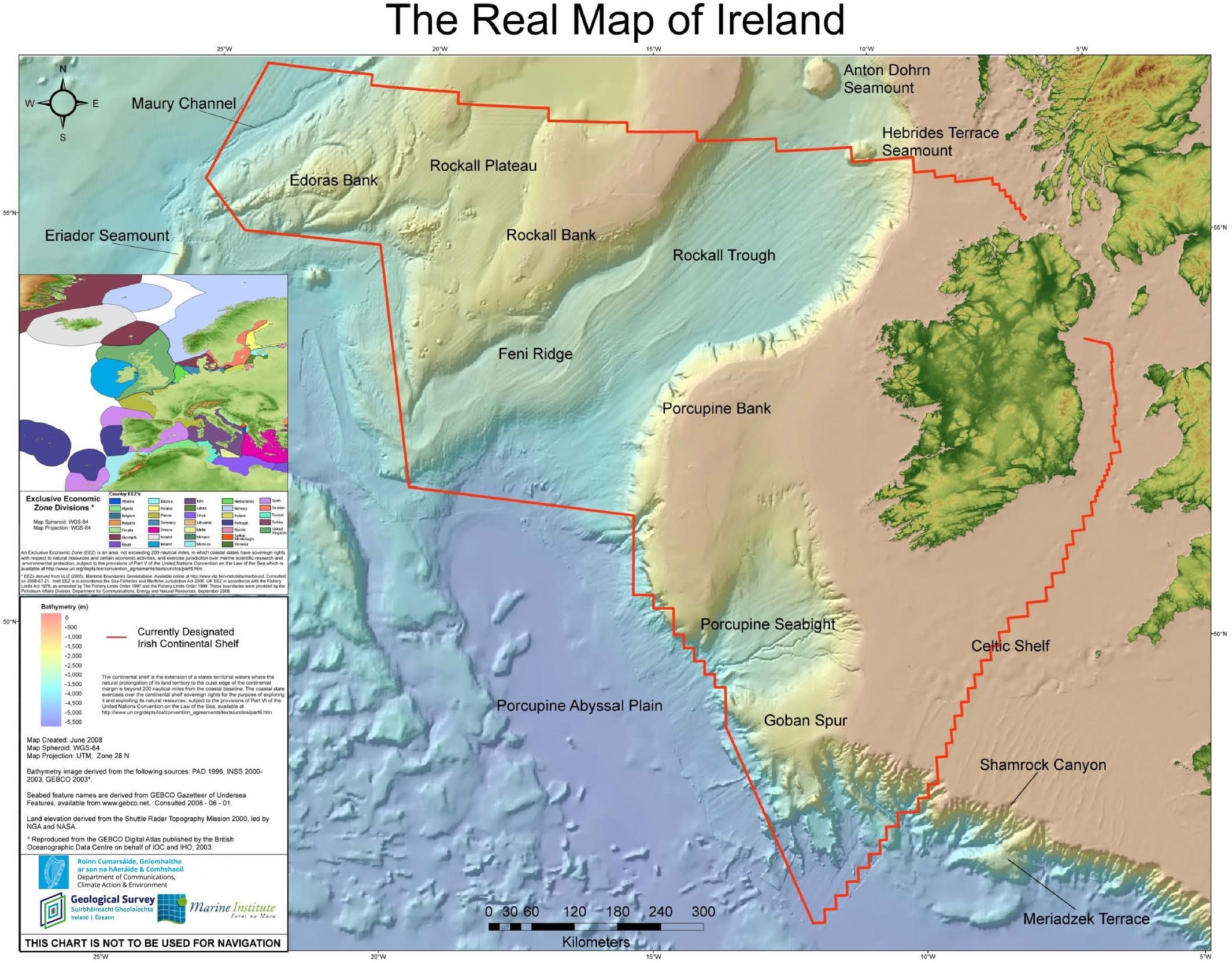

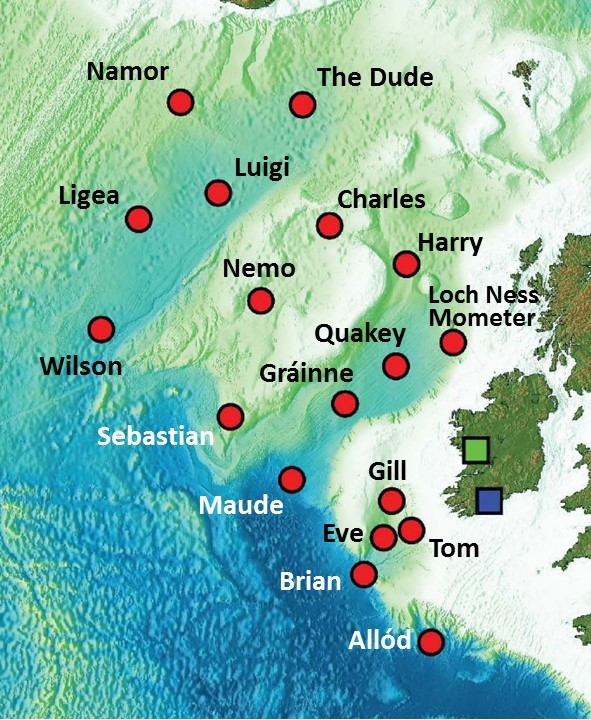

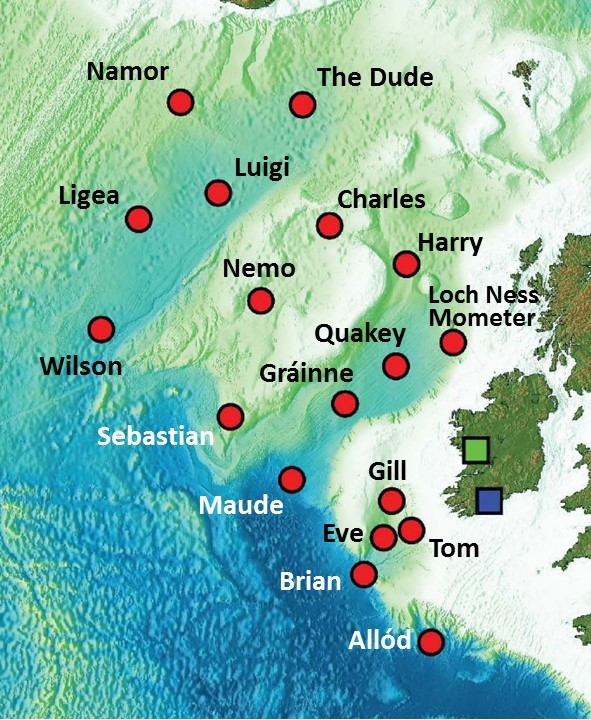

We sampled locations across the deep-water Irish offshore territory, located to the west of Ireland, plus some locations in the UK and Iceland waters. And we thought there were some interesting observations.

The Midnight Zone

The 1-4 km depth range in the ocean is known as the Midnight Zone (AKA the Bathyal zone). No sunlight penetrates here. There are no known plants, because of the lack of light necessary for photosynthesis. All the creatures on our instruments were thus deep-sea animals, of a number of different species.

Octopuses

The most sophisticated sea creatures that came up on the seismometers were octopuses. We found 3 of them on each of the two seismometers deployed at the shallowest depths, Gill at 1062 m depth in the Porcupine Basin (51.9N, 12.75W ) and Charles at 1127 m depth in the northern Hatton-Rockall Basin (58.8N, 15.5W). All the octopuses looked very similar and were probably of the same species.

At the deeper sites in the Porcupine Basin – Tom at 1360 m depth and Eve at 2160 m depth – there were no octopuses, and neither were there any at the deeper sites in the Rockall Trough (Loch Ness Mometer, 2070 m; Quakey, 2840 m; Grainne, 2750 m). Our sampling is sparse but it would suggest that these octopuses live at depths smaller than 2000 m – possibly, only up to about 1200 m.

The octopuses had laid eggs on the plastic surfaces of both seismometers and were there guarding them. The deep seafloor is, for the most part, flat and featureless. The seismometers must have presented the animals with attractive options for nesting.

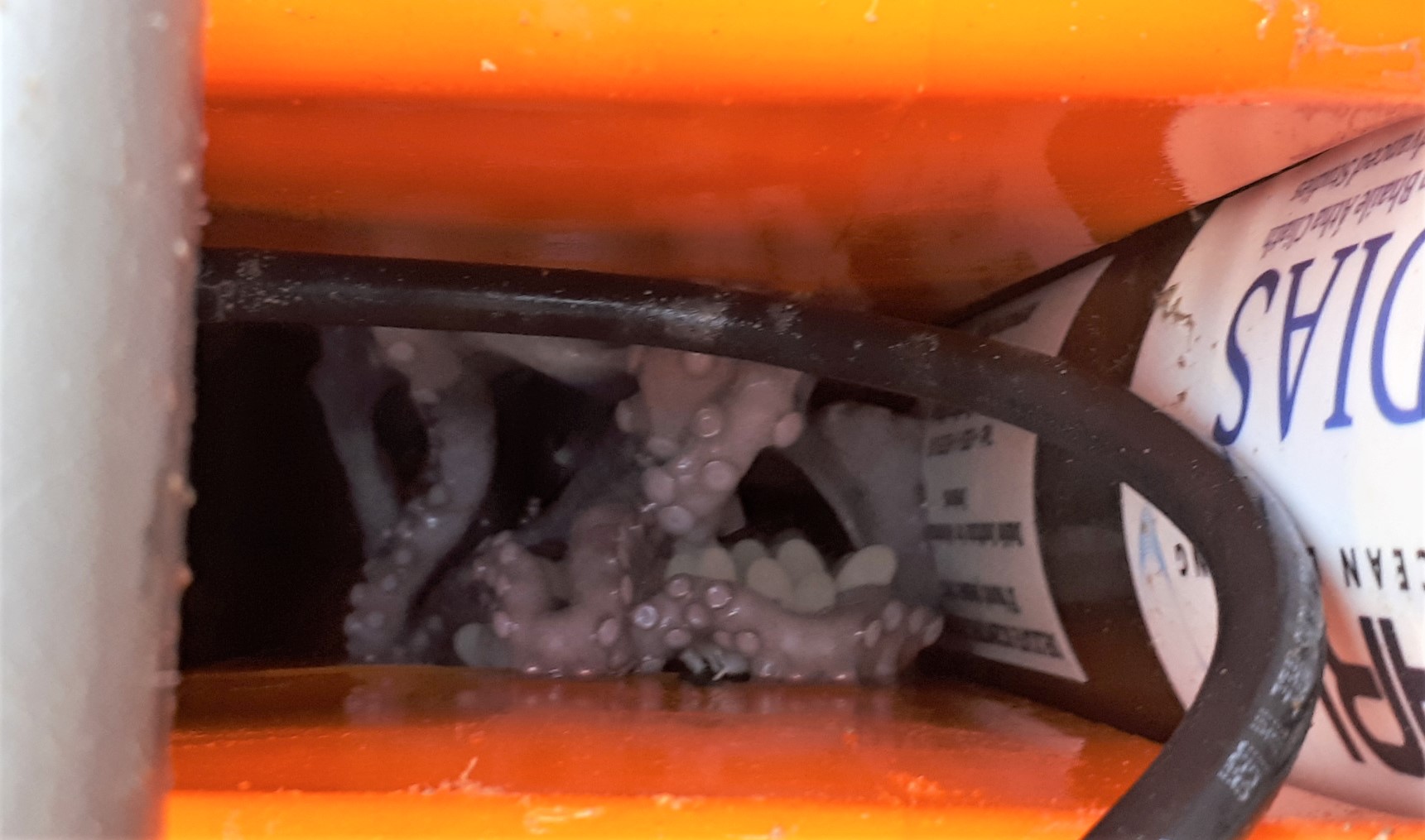

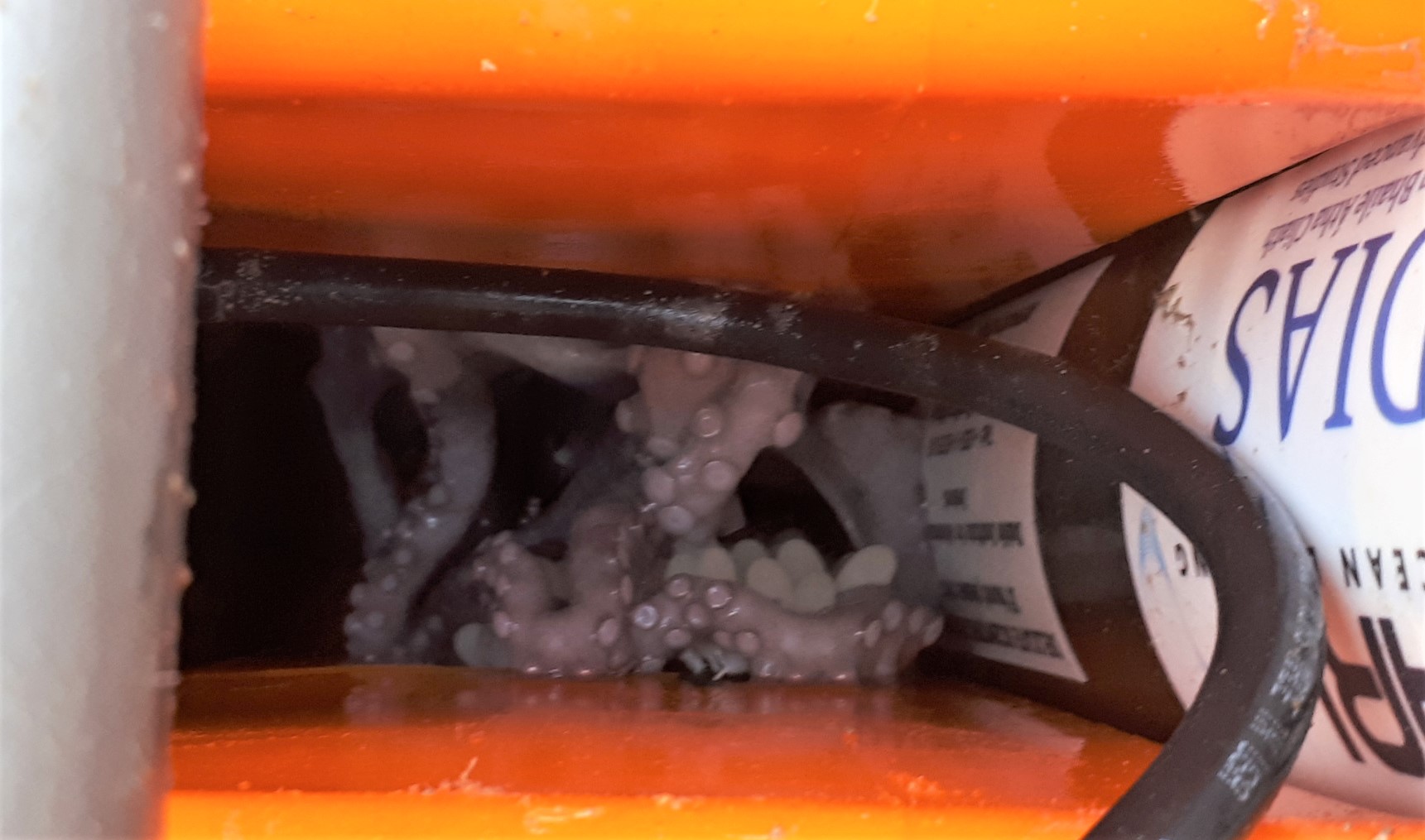

In one case, the eggs were on the outside wall of the structure, and in other cases in the cavities inside and beneath it. The eggs were pearl-white and partly transparent and felt rubbery on touch. They were around 8-15 mm long and 4-5 mm thick. Black tar-like substance covered the surfaces where the eggs attached. A long rope that was folded within the seismometer structure just below one of the nests was covered by the black substance almost entirely.

The octopuses themselves were pale, light brown in colour and had 40-50 cm long arms.

Now, what kind of octopuses were these? We don’t think they were of the species the North Atlantic octopus (Bathypolypus arcticus) as those are typically smaller.

Can anybody help us to find out what species these octopuses were?

Sergei Lebedev, 21/05/2020

Day 18: Land in sight!

After a rough day yesterday we woke up today with a clear blue sky and minimal waves. Looking out of the window we saw the first sight of land after sailing out of the port of Galway 17 days ago. However, the storm caused us some delays which made us miss the morning tide to sail into the Galway port. And thus we spend the whole day slowly sailing into the Galway Bay, with beautiful views on the coasts of Co Clare and Co Galway, including the Cliffs of Moher.

Apart from enjoying the view we had some work to do. The container needed to be packed, the boxes sorted and packed, the labs cleaned and sorted out, the data scanned and backed up. This job became more complicated as the container will stay in the port of Galway while we will return to Dublin tomorrow. Thus everything we might need in the coming weeks will have to come with us to Dublin, as travelling back and forth to Galway is not favourable in the current situation.

After our last diner on the Celtic Explorer we finally sailed into the port of Galway, accompanied by a beautiful sunset over the coast. As the port of Galway is the smallest port in Ireland and it has a very narrow entrance, it is quite a challenge to sail into. However, our highly experienced Captains did not seem to have any trouble sailing us in, being helped by perfectly calm weather and almost no waves.

And thus the Celtic Explorer is now safe and sound back in the harbour, where it will stay until it will sail out on a next mission! However, we have not set foot on land yet, as for safety reasons we will not be able to re-enter the ship once we set foot on land. And thus we spend our last night pretending to still be at sea, spending our evening in our cozy lounge, but without the constant rocking motion of the sea we have become so used to!

Janneke de Laat, 12/05/2020

Day 17: Wind, Waves, Live Video Link-ups

We are now heading back to Galway. The plan was to arrive tomorrow morning but we were slowed down by worsening weather and will now arrive tomorrow evening. The strong winds and waves of over 4 m high reminded us how lucky we were with the weather for most of our expedition.

It was a perfect day, though, for linking up with people onshore and we had two live video link-ups with school classes, one from the St Francis National School, a Primary School in Newcastle, Co Wicklow, and another from St Joseph’s College, a Secondary School in Borrisoleigh, Co. Tipperary. It was great to meet the students, show them the spectacular waves around us, tell them about our project, and answer the many questions they had.

In the evening, the waves subsided. We are now to the west of Co Cork and Kerry and are shielded from the easterly winds by Ireland.

Sergei Lebedev & Janneke de Laat, 11/05/2020

Day 16: No Allod, an Unexpected Visitor and Seabirds #2

At the morning of our 16th day at sea we were ready to pick up our last OBS: Allod. Allod, named after the Irish god of the sea, was our first deployed OBS and would be our last one to retrieve, giving us the longest timeseries of data. At a depth of over 3.8km deep, Allod was communicating perfectly and we gained an accurate location of the instrument. At noon we were ready to release and retrieve Allod back from the sea.

However, Allod seemed to prefer the sea over us and although it gave us a perfect answer every time we send the release code, it answer was always too soon, indicating that it actually did not execute our command. After a full afternoon of communication we had to give up and leave Allod at the oceanfloor for now.

With this last setback this brings our total number of retrieved instruments to 14 out of 18, each with a beautiful set of 19 months of unique recorded data. With the automatic time releaser set in July, we will be back soon to retrieve our four OBSs we had to leave behind: Harry, Nemo, Sebastian and Allod. See you soon!

An unexpected visitor

All of the journey we have been surrounded by a variety of seabirds. After sailing away from Allod we however had a very interesting visitor in our lounge: a Robin! Robins normally do not fly that far out to sea, they prefer forests, parks and gardens instead. This robin somehow made it all the way out to the Atlantic Ocean and found its way into our lounge. As we came across a container ship just an hour before, we expect it to have flew over from there.

Once one of the crew members caught the bird we noticed that the bird was ringed. After holding the bird under the loop (literally), we could read the ring: NHMUSEUM, LONDON. This bird was ringed all the way in the Natural History Museum of London! Soon after we released the bird and wrote the NHM with all the details. They were very happy with our information and will inform us on the track of the bird once they passed the information to the system. Curious what will come out, it seems this little Robin is having quite the adventure!

Continuing on birds, time for seabirds #2!

Seabirds #2: The Northern Fulmar

Last time I gave some special attention to the Northern Gannet, this time it’s time to put another frequent flier in the spotlights: the Northern Fulmar. The northern fulmar, also known as the Arctic Fulmar, has accompanied us frequently over the last two weeks, flying or floating around our ship in groups of 30-50 birds.

At first glance these abundant seabirds can be confused with seagulls, but they are actually family of the petrels and shearwaters. They can be distinguished from gulls by their short neck and large head and their stiff wing action. When flying they only give a series of short, rapid wing beats now and then, gliding low over the surface of the water. They have a wingspan of 102-112 cm and weighs up to 1km. They have a long lifespan, easily reaching 30 years in age, with the oldest bird recorded so far being over 60!

The fulmar is a strong flyer and remains out at sea for most of their life. The only time they spend on land is during breeding season. They breed in loose colonies on narrow ledges on steep, inaccessible cliffs along the coasts around the North Atlantic and North Pacific.

An interesting feature of the northern fulmar is the oil they create in their stomach called the proventriculus. This oil has two purposes: it can be sprayed out to defend itself from predator birds (the oil will gum up their wings causing them to plunge and die) and it can be used as an energy source when they are on long flights or to feed their young. Also this oil is what gave them their name. Their name comes from two old Norse words: “fúll” meaning “foul” and “már” meaning “gull”, referring to this bad-smelling stomach oil.

Thank you for flying with us!

Janneke de laat, 11/05/2020

References

- https://oceanwide-expeditions.com/to-do/wildlife/fulmar-1

- https://www.npolar.no/en/species/northern-fulmar/

Day 15: Brian and Eve.

Last night, we reached seismometer Eve and triangulated its location. By the time we were done, it was dark. It was now too late to release it, as we would not be able to see it in the water.

We stayed at the site till the morning and sent the release command then. Thirty five minutes later, Eve completed her 2160 m ascent from the seafloor and popped up at the surface.

Eve is a clever wordplay on ‘eavesdropping on the Earth’ by the students of St. Patrick’s College, Gardiner’s Hill, Cork City, Co Cork. (teacher: Erin Keogh).

Our next stop was at the site of seismometer Brian. Brian was deployed at a depth of over 3.9 km and we had little hope of triangulating it. In the past, our transducers had never managed to register signals from seismometers that deep. Although the ocean-bottom seismometer can hear the transducer very well, so that it can receive the command to detach from the anchor and come back to the surface, the signals sent by the seismometer itself are more difficult for the transducer to pick up, due to the near-surface noise in the ocean.

Today, the ocean was calm and we set a personal record. We triangulated the OBS at a nearly 4 km depth! We ranged it at 6 sites and received a very clear signal from the seafloor every time.

When we sent the release command, we estimated it would take Brian just over an hour to make it to the surface. And, right on time, it was spotted just in front of the ship (not a coincidence – we had moved the ship where the triangulation told us the seismometer was!)

Brian was named by the SEA-SEIS Team itself. It was after Brian Jacob, who led the work on the continental nature of the basins west of Ireland, which led to the Irish territory increasing by about a factor of 10. Brian Jacob was the Senior Professor at the Geophysics Section, DIAS, from 1989 until 2001.

About 90% of the Irish territory is offshore. This territory was attributed to Ireland under the international Law of the Sea because it was shown that continental crust extends continuously from Ireland to the underwater Edoras Bank, hundreds of kilometres to the west.

Sergei Lebedev & Janneke de Laat, 09/05/2020

Day 14: Gill. Tom. Octopuses.

We started triangulating seismometer Gill before dawn, at 5 am. This was timed so that by the time the triangulation is finished and the seismometer is released and reaches the surface, there is already enough light for us to spot it.

Everything went to plan, and Gill came up happily. It was a misty morning, and for a moment it looked like thick fog was coming down over the water. We were worried that we may not be able to see the seismometer, but it popped up very close to us, less than 100 m from the ship.

Hello, Gill!

Seismometer Gill was named by the Grange Community College, Donaghmede, Co. Dublin (science teacher: Niall Nolan) after that essential organ of aquatic animals, from fish to octopuses. Speaking of… but more on that in a minute.

Our next seismometer, Tom, was not far and we reached it just after lunch, also retrieving it with no problems.

Seismometer Tom was named after Thomas Crean, the Irish seaman & explorer, by the students of Largy College, Clones, Co Monaghan (teacher: Colette Smith, proposed by Eimear Courtney). Welcome back, Tom!

Octopuses

And now, back to Gill. This seismometer came up from the depth of 1050 metres, and it brought up some passengers – 3 octopuses! The plastic structure of the instrument was used by two of them to lay their eggs on.

The octopus on the right is a female guarding her eggs.

The octopus on the right is a female guarding her eggs.

And deep inside the orange float of the ocean-bottom seismometer, there was another octopus guarding her eggs.

We would prefer not to disturb the animals but – sorry, guys, we must have our seismometer back! All the visitors put back into the ocean, we sail on to our next destination, which we should reach around 9 p.m.

Sergei Lebedev, 08/05/2020

Day 13: Maude

Ahoy, Maude!

Seismometer Maude was named after Maude Delap, the Irish marine biologist, by the students of St Joseph’s College, Borrisoleigh, Co Tipperary (teacher: Mary Gorey). This morning, it has been recovered from a 3.8 km depth.

Ahoy, Pilot Whales!

As we were communicating with Maude, dozens of pilot whales came to socialize next to our ship. Our transducer picked up a constant squeaky chatter of the whales. Were they curious about the signals that the transducer itself emitted when we were talking to Maude?

Sergei Lebedev, 07/05/2020

Day 12: Sebastian Under the Sea

After another lovely breakfast we made our way to the wetlab to get ready to retrieve Sebastian, OBS number 12. With our improved triangulation method we got a very precise location of the seismometer and released the instrument just above the expected surfacing location.

Sebastian heard our release code loud and clear and responded as quickly as possible. Too quickly. So quickly that it seemed to have forgotten to actually execute the command we send it. It did not release and after many times and variations we had to give up. After adding another few points to our triangulation (see blog day 11) we had to sail away, sad to leave Sebastian behind under the sea.

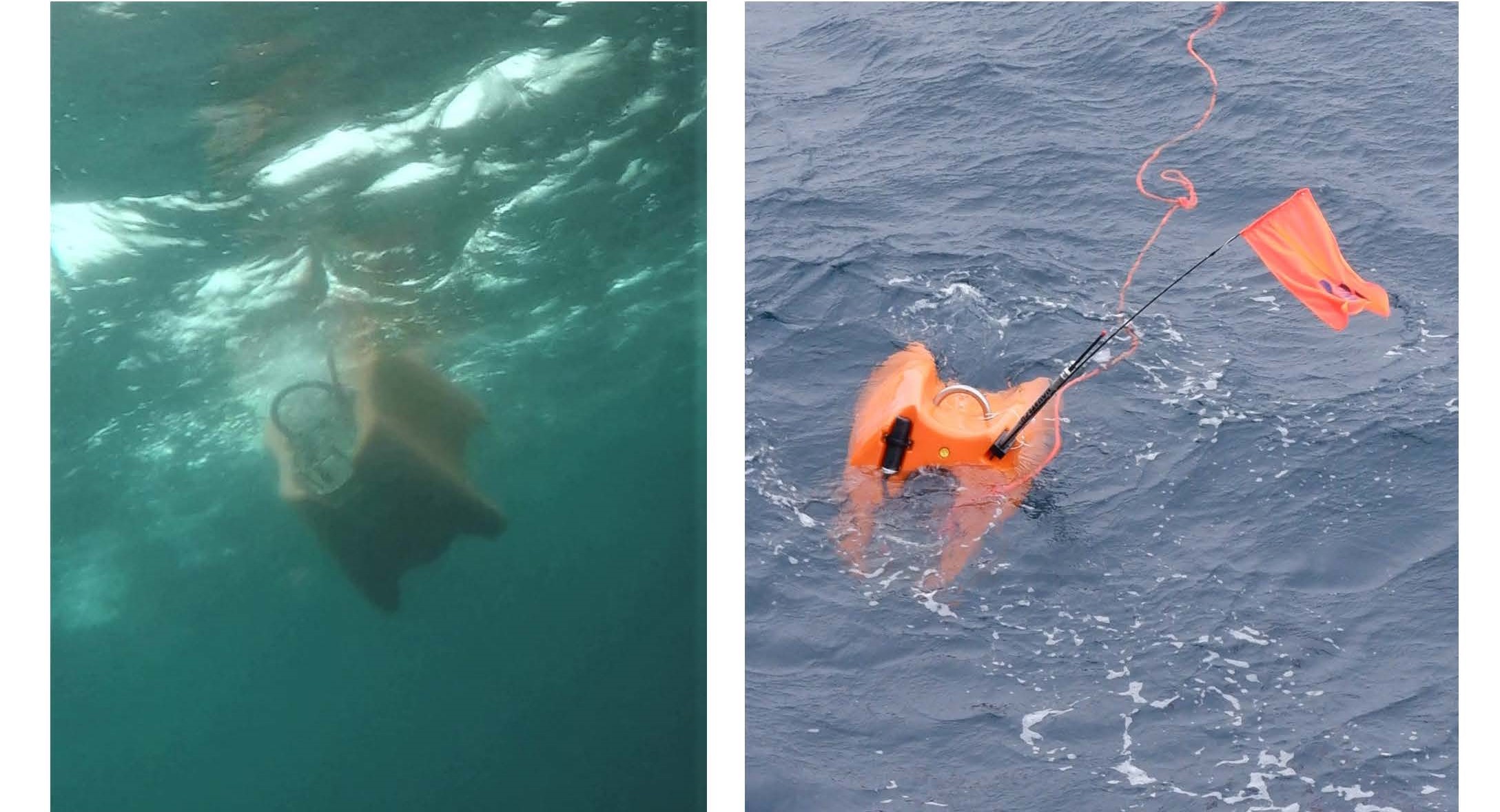

On a positive note, while looking for Sebastian, we were joined by a big pod of pilot whales. The pod existed out of at least 30 animals and they kept surrounding the ship the full morning until we to sailed away. Lets find out some more about these animals that are keeping Sebastian company.

Pilot whales

The first time we spotted these curious creatures was when we retrieved Grainne, our first OBS. We actually heard them before we saw them, as our acoustic transducer picked up their communication while listening to the response of the seismometer. It was a high whistling sound, and a special experience*. Shortly after the pilot whales were spotted by the crew and we could enjoy them swimming around our vessel.

* Unfortunately the frequency of the communication of pilot whales is too high for our seismometer to pick up. We are, however, able to pick up fin whale and blue whale communication.

So what do we know about these sea mammals? The first interesting fact is that, despite its name, the pilot whale is actually one of the largest members of the dolphin family. The name is believed to have arrived from the fact that each pod follows a ‘pilot’ in the group.

Pilot whales are dark grey with a large bulbous forehead, growing up to 6m in length. There are two separate species of pilot whales: the long finned and short finned. The long finned pilot whale populates the Southern Ocean while the short finned lives in the North Atlantic. The pilot whales visiting us are thus short finned pilot whales!

Pilot whales live in stable family groups of 20-100 whales and the offspring stays in their mother’s pod. Males spend a few months with another pod to mate, whereafter returning to their own pod. Females calve every 3-5 years and can live up to ~60 years, while males only reach 35-45 years in age.

Traditionally pilot whales were hunted for bone, meat, oil and fertilizer. Luckily they are now protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and are only sustainably hunted at the Faroe Islands and Greenland.

Happy to have met you!

Janneke de Laat 06/05/2020

References:

- https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/native-animals/marine-mammals/dolphins/pilot-whales/

Day 11: Finding Nemo Part 2

Overnight we traveled back to the Hatton basin for a second try at recovering Nemo. In the morning we range the instrument to measure its distance from the ship and try to release it several times, however this seismometer is stubbornly stuck on the sea-floor.

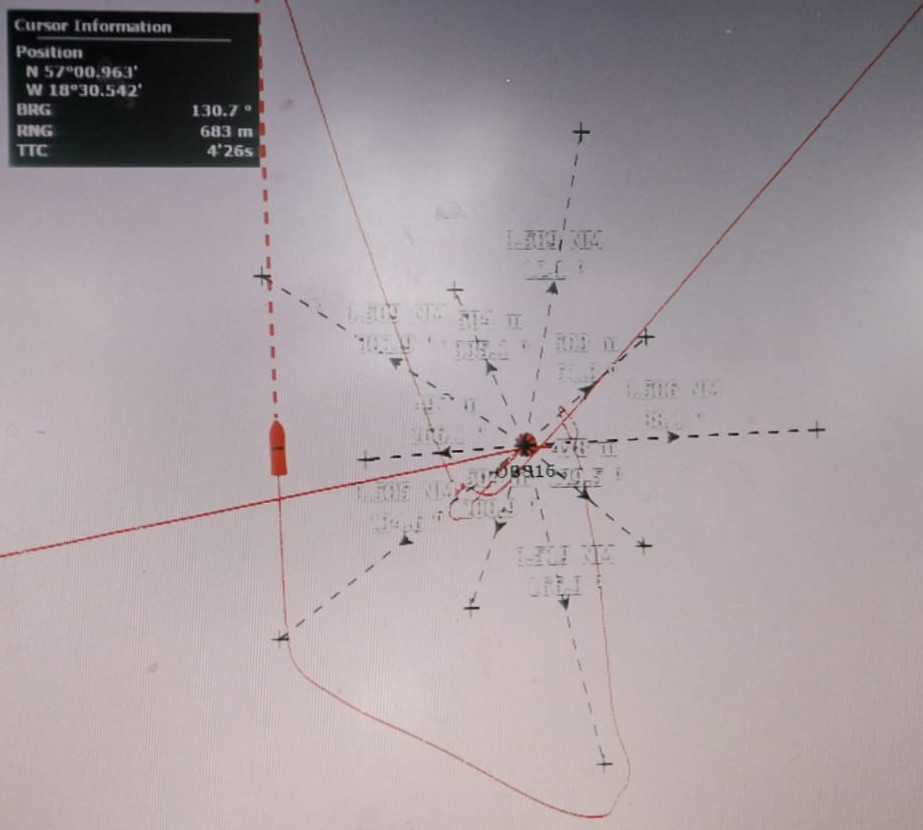

Triangulation:

Nemo’s batteries will not last forever so in the hopes that someone will be able to organize a rescue mission at some later time we decided to get Nemo’s position on the sea-floor as accurately as possible. To triangulate we choose 11 points around the estimated location , move the ship to each one and measure the range. The process takes several hours. We triangulate Nemo’s location as the intersection of all these measurements, then move the ship to this position so we are directly above the OBS and range one last time. If Nemo is directly below then this last measurement should be equivalent to the water depth. The Celtic Explorer also has the capability to measure the water depth and when the two measurements are compared they match!

With the triangulation finished we have one last attempt to release Nemo but it still refuses to join us at the surface. Eventually we have to leave and steer towards the south where, tomorrow, we will start the recovery of Sebastian.

David Craig, 05/05/2020

Seabirds #1: The Northern Gannet

Since the moment we sailed out of the port of Galway, we have been accompanied by different types of seabirds. Time to give them some special attention. Up first, The northern gannet.

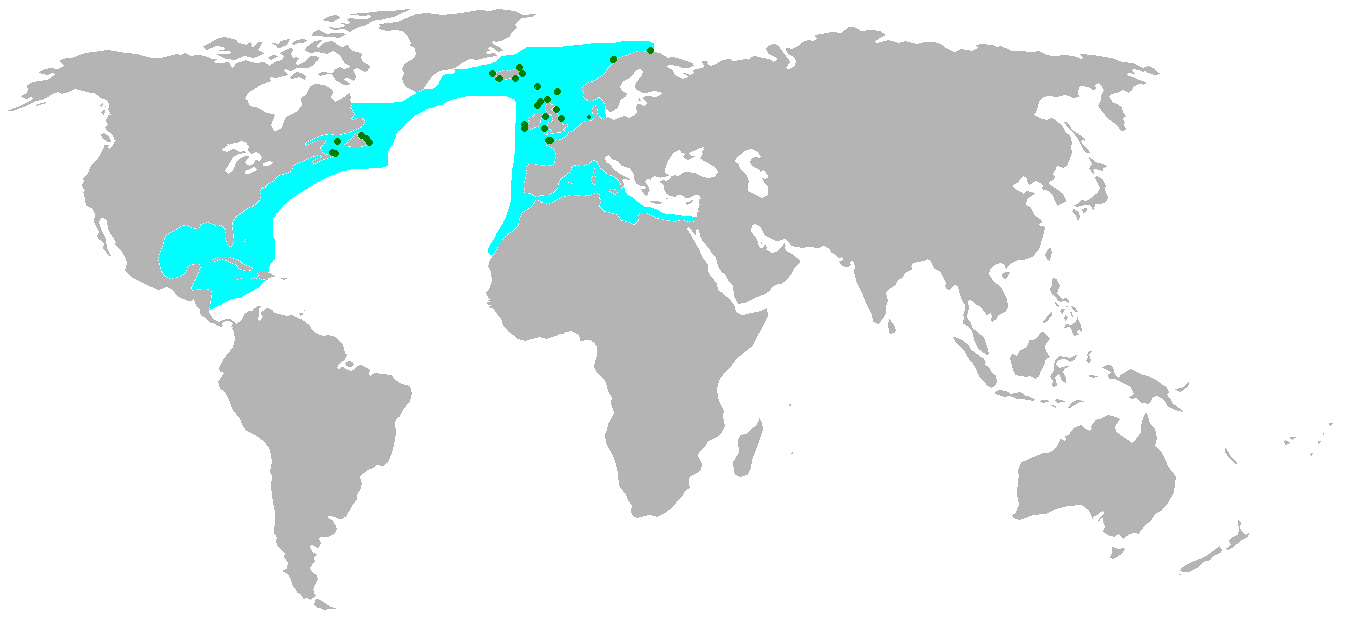

With a wingspan of 170-184 cm the northern gannet is the largest seabird which is native to the North Atlantic. In length it can get up to 110 cm, almost the size of an albatross, and weighs up to 3.6 kg.

Adult birds are easy to recognise by their white body, black wingtips and yellow head. Their feathers are waterproof, allowing them to spend long periods in the water. Juvenile on the other hand are uniformly brown over the five years it takes them to grow up they transition to white and show a patchwork of dark and light feathering.

The northern gannets fly with deep, slow wingbeats when searching for fish. Normally they fly up to 150 km over sea when searching for fish, but this can increase to up to 600km! When a prey is spotted they plunge-dive from about 30m height into the water with a speed that can reach up to 96 km/h, diving down to 1.3m deep in the water.

In blue the flying range of the northern gannet, in green their breeding spots.

The only time northern gannets spend on land is on their nests, which are placed on oceanside cliffs. The breeding range of the northern gannet is on both sides of the North Atlantic, including the East coast of Canada, Iceland, Ireland and the UK. They normally nest in large colonies and can be remain located at the same place for hundreds of years.

Fun fact: The oldest recorded northern gannet was found in Quebec, aged at least 26 years old!

Thank you for flying with us 🙂

Janneke de Laat 04/05/2020

References:

- https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Gannet/

- https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/birds/seabirds/northern-gannet

Day 10: Wilson.

Wilson! We started the morning with the triangulation of seismometer Wilson and then recovered it from its deployment site, 3 km below the sea surface. The OBS was still recording as we retrieved it. The battery lasted well past its nominal 14.5 month capacity, and Wilson got 19 months of data for us!

Wilson was named after the ball from “Castaway†by Kingswood Community College, Dublin 24 (teacher: Jessica Lynch, geography). We remember our live video link-up with the school from our ship in 2018!

Wilson was actually named twice – also after Brian Wilson, of the “Good Vibrations†fame, by Presentation College Bray, Co Wicklow (teacher: John Bourke, science). It was another great live video link-up with this school from our ship in 2018. (And, if we may add one ourselves, we should not forget Tuzo Wilson, a geophysicist who made important contributions to the theory of plate tectonics!)

Whale Blows

As we are triangulating and recovering Wilson, blows of fin whales are popping up every once in a while a few hundred meters from the ship.

What are blows? As the whales come to the water surface to take a breath, they expel used air through their blowholes. The blowholes are similar to nostrils of people and other mammals, except that the whales have them on the top of their heads. The resulting spray, or the blow, is made mostly of condensing water vapor, also with a bit of water from the top of the blowholes. The blow rises up a few metres high, like a fountain, and can be seen from far away in the ocean.

SEA-SEIS Music

Finally, both of the schools that named Wilson also participated in the SEA-SEIS Song and Rap Competition. You can hear their prize-winning entries at https://sea-seis.ie/sea-seis-rap-18

And to hear and see selected entries from both the SEA-SEIS Song and Rap and SEA-SEIS Drawing competitions put together, see our favourite video above!

Sergei Lebedev, 04/05/2020

Day 9: Ligea.

Ah! Oh gods, what sight is here? Ligea, siren of the sea!

This ocean-bottom seismometer was named by the students of Istituto comprensivo don Lorenzo Milani, Lamezia Terme, Calabria, Italy.

The story of Ligea is somewhat tragic – we are talking Greek myths here. According to the myth, Ligea and her sisters Partenope and Leucosia were friends of Persephone and they were all together when Hades, the god of the underworld, kidnapped Persephone to make her his wife and the goddess of the underworld.  Persephone’s mother Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, was inconsolable, searched for her daughter ceaselessly and, among other desperate measures, turned Ligea and her sisters into mermaids, as punishment for not preventing her daughter’s abduction. Living her life as a siren from then on, Ligea met her tragic end when she threw herself into the sea from the top of a cliff, following the passage of Ulysses’ ship that emerged unaffected by her bewitching song. The waves of the Tyrrhenian Sea brought her lifeless body to the shore of Calabria, near the ancient city of Terina.

On a positive note, Ligea came to be the revered personification of ancient Terina, next to which there is now a beautiful city of Lamezia Terme. A statue of Ligea graces a square in the historic centre of Lamezia Terme. And now her name has also been immortalized as the name of a broadband, ocean-bottom seismic station, which will remain in seismic data archives indefinitely.

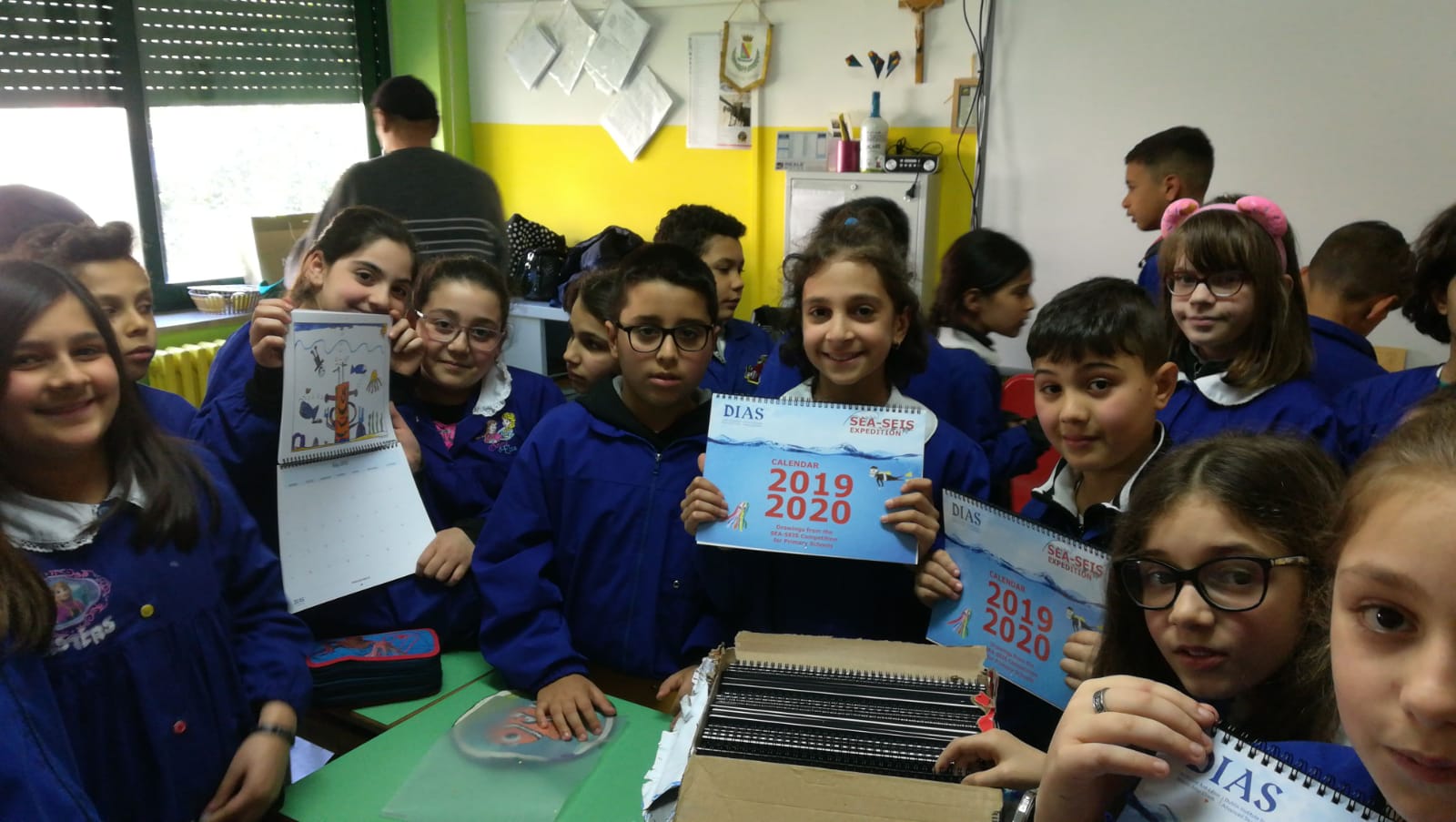

SEA-SEIS Art

The students of Istituto comprensivo don Lorenzo Milani, Lamezia Terme, not only named the seismometer but also sent their lovely art to the SEA-SEIS Drawing Competition.

The students’ drawings were featured in the SEA-SEIS Calendar, sent to every artist as a prize.

Data, data, data

Back to the Celtic Explorer, we are now in possession of the unique data collected by 8 of our seismometers – on their original waterproof memory sticks and on our computers. One seismometer recorded for 17 months, and the others – for 19 months, until the day we picked them up!

Sergei Lebedev, 03/05/2020

Evening 8: Namor.

Greetings, mighty Namor! Just before sunset, we recover the ocean-bottom seismometer Namor, named after a Marvel superhero Namor the Submariner by the students of Glenstal Abbey School, Murroe, Co Limerick (teacher: Cathal Reid).

The mutant son of a human sea captain and a princess of the mythical undersea kingdom of Atlantis, Namor possesses the super-strength and aquatic abilities of the Homo mermanus race, as well as the mutant ability of flight, along with other superhuman powers.

This was our northernmost station, at 61.5N. We are now going South.

As we complete the retrieval of our two northernmost seismometers in one day, we are treated to a special show.

Can you spot the whale?

Sergei Lebedev & Ee Liang Chua, 02/05/2020

Morning 8: The Dude.

The Dude is one of our two northernmost stations, just south of Iceland. As we were moving north, the nights got shorter and shorter. Here is last night’s 11 pm sunset, seen from the bridge of the Celtic Explorer.

We arrive to the site at 5 am, just before dawn. This was timed so that by the time the seismometer is up to the surface, there is enough light for us to see it.

And… the Dude abides! Release command, swift (around 1 m/s) ascent to the surface… and we spot the orange flag from the bridge. His Dudeness is welcomed aboard.

The Dude (short for the Dunamase Dude) was named by the students of Dunamase College, Portlaoise, Co. Laois (teacher: David Thompson, Geography Dept.)

Like with the other OBSs we have retrieved over the past week, it turns out that the batteries powering the seismometer and data logger have lasted well past their nominal capacity of 14.5 months. Gráinne, the first to be recovered, recorded for over 17 months and all the others did even better, recordings until the time of recovery (~19 months). More data – excellent news!

“Bridge, Wet Lab. Dunker Out.”

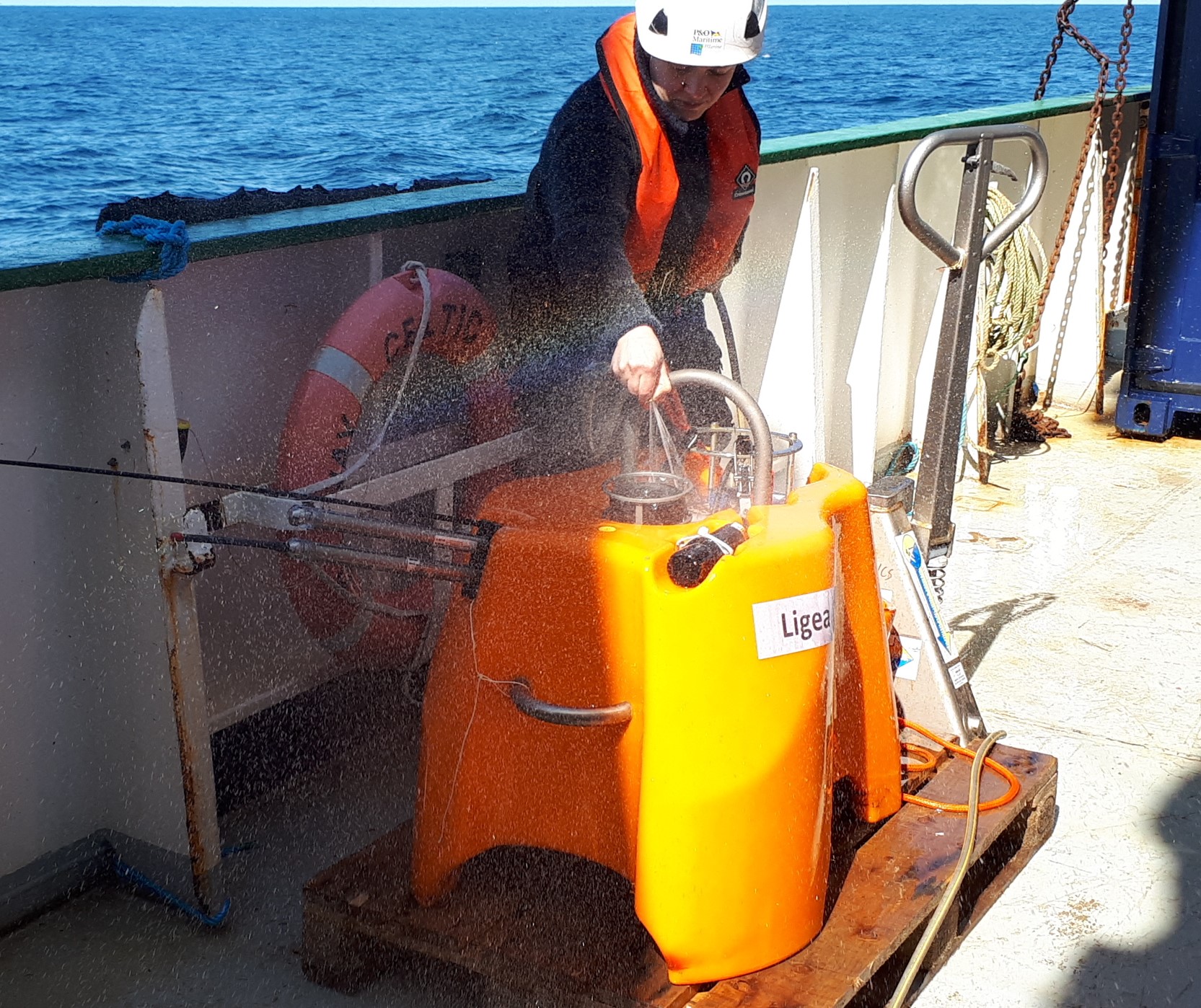

How do we communicate with the seismometer on the seafloor? We put the transducer (AKA dunker – a device that can emit acoustic signals to the OBS and receive them from it) into the water overboard on a 50-m long cable. It is important that it goes fairly deep into the water, below the noisy waves and the noisy ship.

But a research vessel presents a danger to the transducer and its cable overboard. The ship maneuvers – for example, maintains the same position, as measured with GPS, in a current – using propeller-shaped thrusters, and these can suck in and rip the transducer off its cable. To avoid that, we keep constant communication with the bridge and keep the Captain informed of what we are doing over a walkie talkie. If the dunker is out of the water, the thrusters can be turned on. “Bridge, Wet Lab. Dunker Out.”

Sergei Lebedev, 02/05/2020

Day 7: Luigi.

Seismometer Luigi was named by the students of Lycée Français d’Irlande, Dublin (Rayan, Tristan, Ethan, Niv, Elissa; teacher: Céline Tirel). It was after Luigi Palmieri, an Italian physicist and meteorologist known for his studies of the eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, research on earthquakes and work on early seismographs. Or was it also a playful reference to Luigi, the brother of Mario, from a certain video game?

Luigi came up happily, even though it had a long way to go – it was deployed at a depth of over 2.8 km. It was spotted at the surface about 40 minutes after receiving our release command. Ciao Luigi!

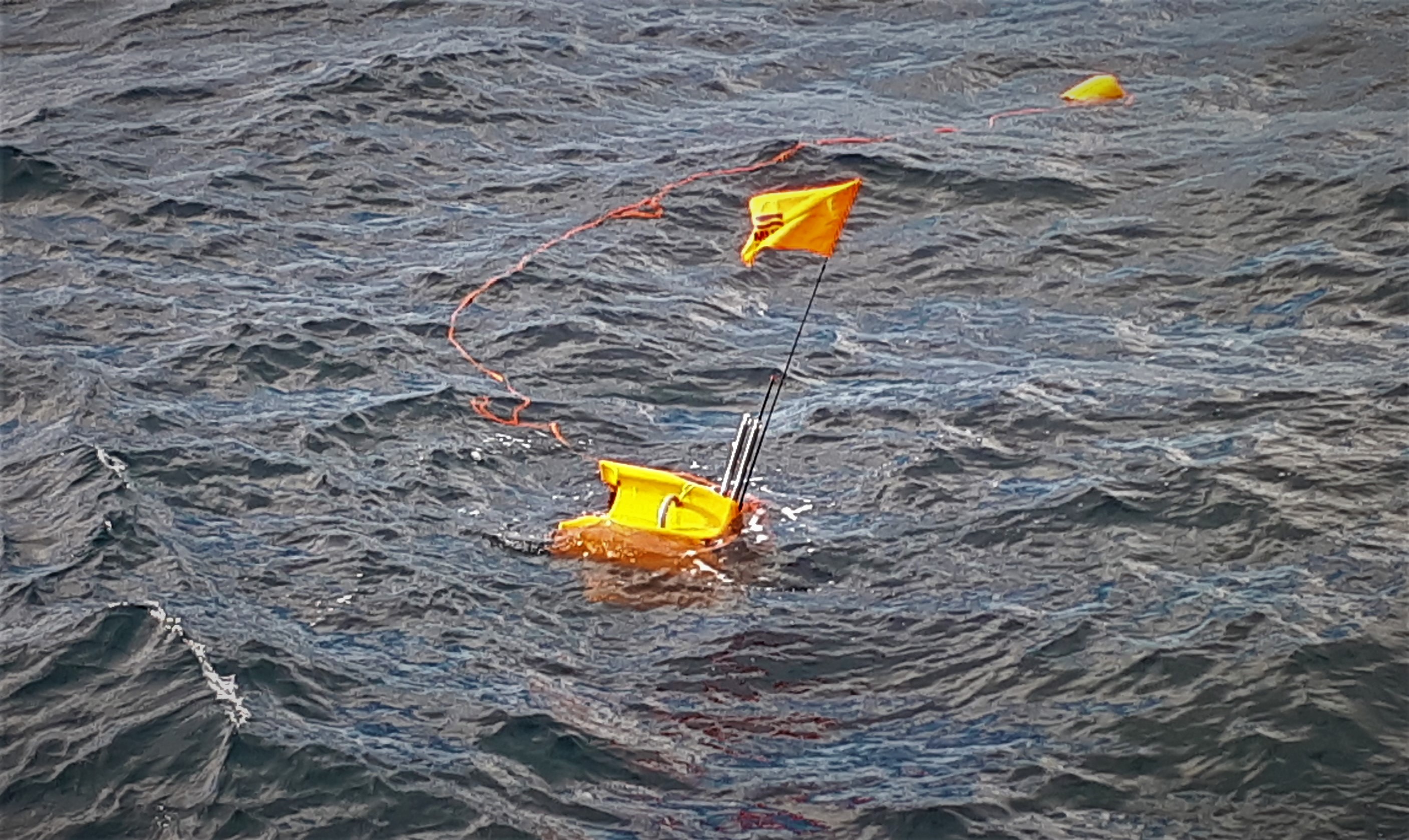

Fun with Flags

Incidentally, how do we spot the instruments after they come up? They have flashing-light beacons and they have radio beacons. And yet, the most reliable way of spotting a seismometer bobbing at the surface has been by their bright orange flags. Here’s to old-fashioned maritime technology!

Wij houden van Oranje!

Sergei Lebedev & Janneke de Laat, 01/05/2020

Day 6: Finding Nemo.

This morning, our goal was to retrieve seismometer Nemo. Finding it was easy, it was waiting for us just where we left it, in the middle of the Hatton Basin in the far reaches of the Irish offshore territory.

The Hatton Basin is a trough between the Hatton and Edoras Banks to the west and the Rockall Bank to the east. All of these features are underwater, but the map of bathymetry (underwater topography) shows the banks to have higher seafloor elevation compared to the basin. The Hatton Basin is shared between Ireland, which has its southern part, and the UK, which has the northern part. The border between the two parts is just north of where Nemo is.

We established contact with Nemo and ranged it. It responded happily. But when we sent it the Release-the-anchor command it replied, a few seconds later, that it was still sitting on the seafloor. More Release commands – the same answer.

This is not what should happen. What could have gone wrong? Hard-to-get-out-of mud on the seafloor? Unusual sediment accumulation around the seismometer? Batteries unexpectedly losing power? We will need to find out later but have to move on now.

As we set course further north, towards Iceland, we are accompanied by birds of the North, the Arctic fulmars.

Sergei Lebedev & Janneke de Laat, 30/04/2020

Evening 5: Charles and friends.

A nice, easy recovery of seismometer Charles in a gentle evening breeze.

Hello, Charles. Hello… wait, who are your little friends?

3 octopuses! (One did not wish to be photographed and went straight back into the water.)

The ocean-bottom seismometer Charles was named by the students of St Muredachs College, Ballina, Co.Mayo (teacher: Cliodhna Boyce) after Charles Richter, the creator of the Richter magnitude scale that quantifies the size of earthquakes and Charles Darwin, the naturalist and marine biologist.

Sergei Lebedev & Ee Liang Chua, 29/04/2020

Day 5: Data!!!

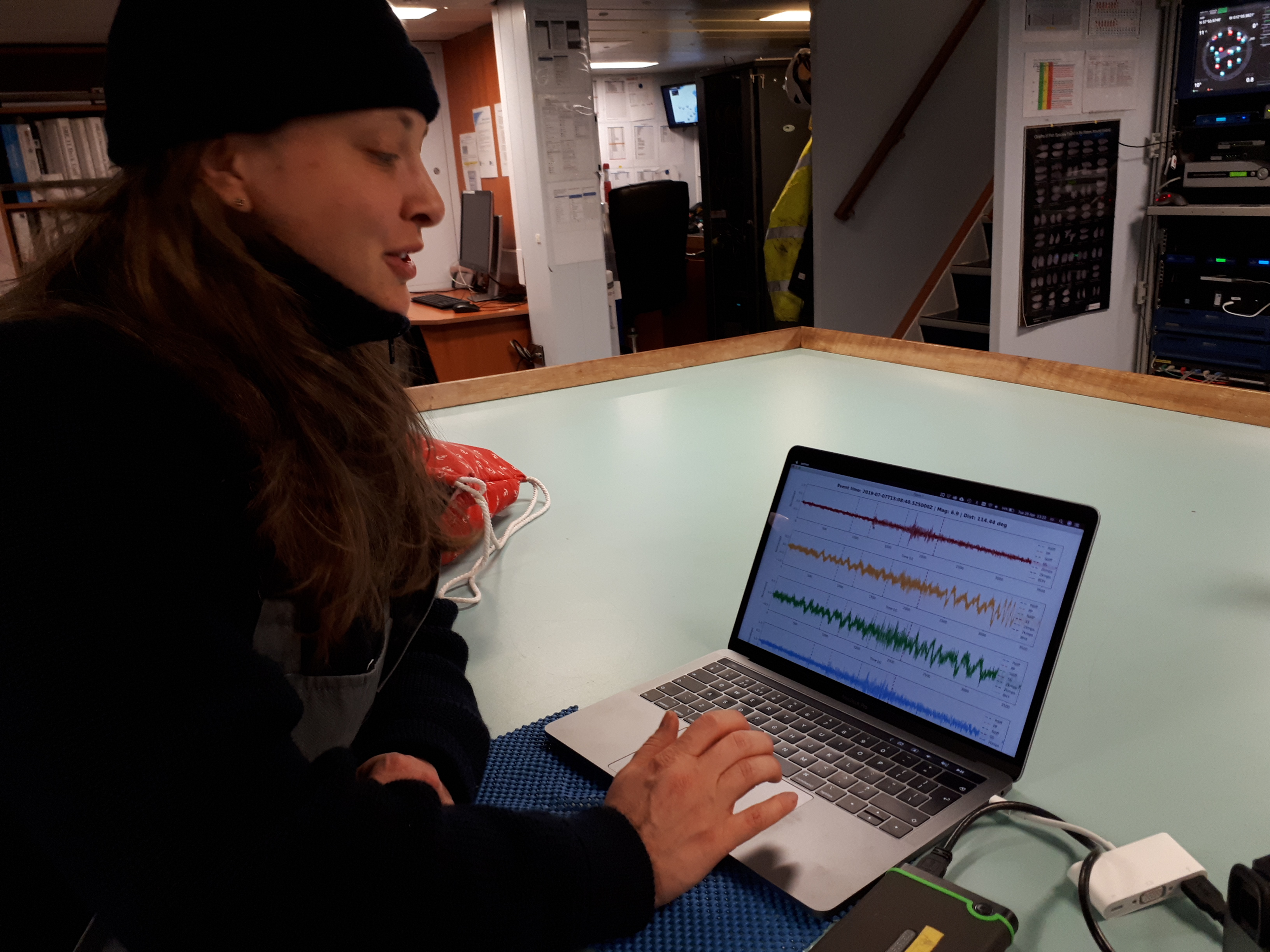

The first glimpse into the unique new data recorded by the seismometers on the North Atlantic seafloor! A seismogram of an earthquake in SE Asia, on the other side of the world, recorded by our ocean-bottom seismic station Quakey.

Maria Tsekhmistrenko of the SEA-SEIS team has plotted 4 traces on her screen. The wiggly line at the top is the recording of the vertical motion of the seafloor. On this trace, we see clearly the arrivals of different types of seismic waves – body waves and surface waves.

The two wiggly lines below are the horizontal components of the seafloor motion. There is more noise on the horizontals, as is usually the case at both terrestrial and ocean-bottom seismic stations. Filtering and further processing of the signal from these components will help us see the earthquake signal more clearly. Finally, the bottom trace is the acoustic recording made by the instrument’s hydrophone.

We already knew we had a lot of data recorded but it’s great to see a seismogram that looks just as it should! Quality data!

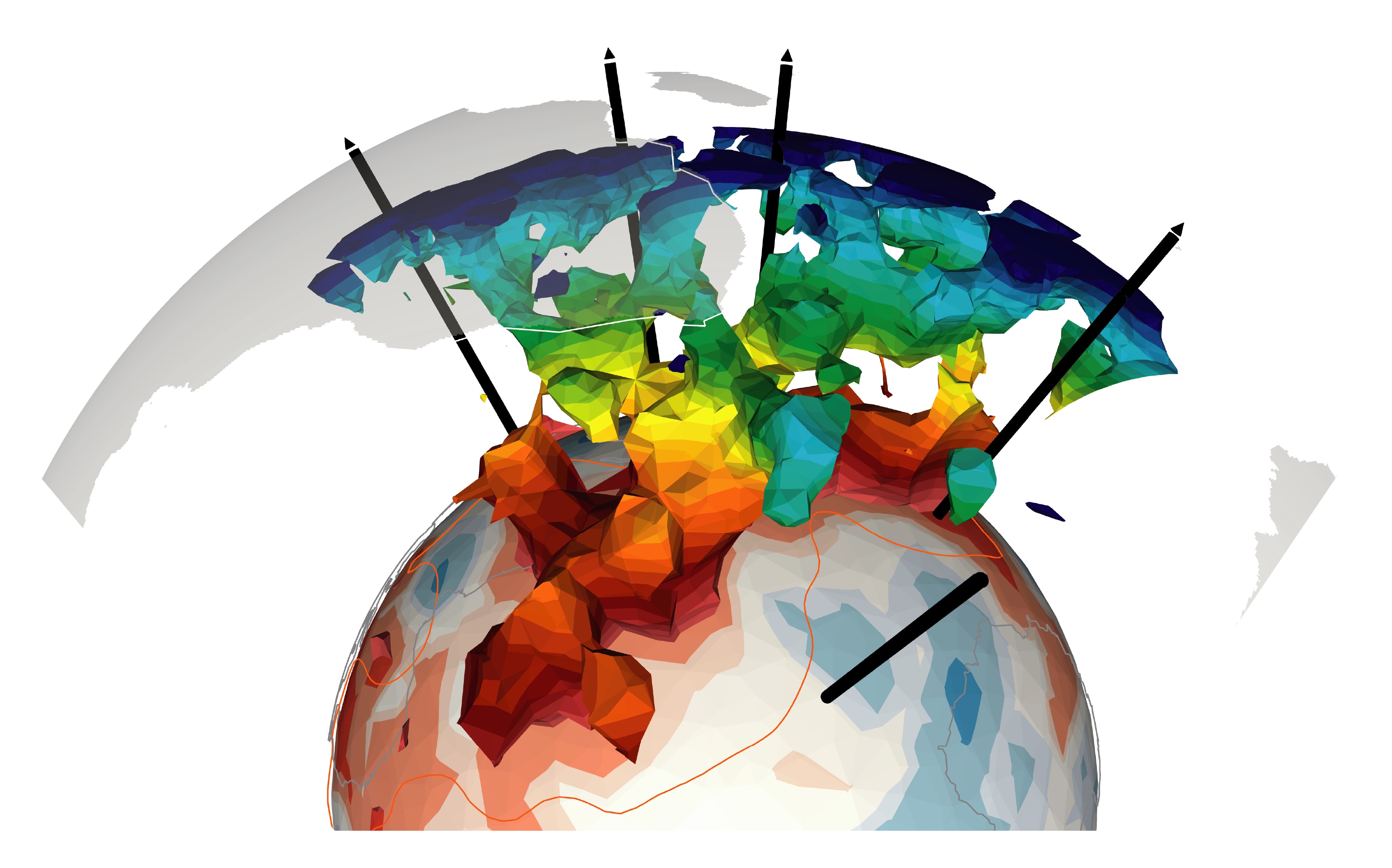

Why are we excited to get recordings of remote earthquakes in new locations? One thing the SEA-SEIS team are specialists in is seismic tomography. The body and surface waves propagating from earthquakes to stations accumulate information on the Earth structure that they traverse on their way. Using many earthquake-station pairs, we can compute a 3-dimensional model of the Earth’s interior – like a 3D X-ray of the Earth.

The key to the success of seismic tomography is data sampling, and in the North Atlantic basin it is sparse, due to the lack of seismic stations. Our new data will fill the gap to a large extent. It should bring exciting discoveries on the structure of the tectonic plate that Ireland sits on, convection of the hot mantle beneath the plate, and the origin of the volcanoes such as those at the Giant’s Causeway.

Sergei Lebedev, 29/04/2020

Night 4: From Dusk till Dawn

A long, frustrating night for the SEA-SEIS team. Arriving to the seismometer Harry two and a half hours before dark, we get in touch with the instrument and send a Release command. Harry hears us but reports that it is still on the seafloor. We range the instrument and it gives us the correct values of its depth. All in order? But as we keep sending the Release command, the OBS remains on the seafloor.

It is now dark. We disable the release mechanism, to save its battery power, and pause for a few hours.

… till dawn.

Before dawn, we re-start communicating with Harry. After more than 65 Release commands, after trying everything else and after a long WhatsApp call with Arne, the K.U.M. engineer in Germany who had led the development of the instrument, we have to accept it: Harry may have decided to stay on the seafloor for a while longer.

Was Harry very unlucky to land and get stuck in mud? Did a highly unusual number of sea creatures colonise the instrument or managed to squeeze into the space that the releaser needs to detach from the anchor? It is now 10 am and we have to go full steam to the next site, to make sure we are there before dark.

Bye for now, Harry.

Sergei Lebedev, 29/04/2020

Day 4: Loch Ness Mometer

We started the day with the triangulation and retrieval of our 3rd seismometer, also known as the Loch Ness Mometer. It was named by Scoil Mhuire, Buncrana, Co Donegal (teacher: Denise Dowds, geography; proposed by Marie Barr).

Good to have you back, Nessie.

Looking at the up-close photos of the just-recovered seismometers, can you spot the difference between Loch Ness Mometer and the first two? (More on this in the coming days!)

Sergei Lebedev, 28/04/2020

Evening 3: Welcome back, Quakey! – and the triangulation

In the evening we retrieved the second of our 18 seismometers, Quakey. Sent the acoustic signal from the ship, received one back from Quakey. But before sending the Release command, we first wanted to triangulate the instrument’s location.

We know exactly where we dropped the ocean bottom seismometer (OBS) when we were deploying it. But it may have drifted by a few hundred meters with the ocean current on its way down to the seafloor. And for seismic measurements, we need the location of the instruments to be as precise as possible. We triangulated some of the locations on the deployment expedition in 2018, but for others it did not work because of rough weather.

How do we triangulate? We first range the instrument (measure the distance from it to the ship) at the location it was dropped in 2018 and then go around it on the ship and range the instrument at 3-4 points 300-500 m away from the deployment point. With that, we can calculate the actual location of the OBS on the seafloor.

All the measurements recorded, now it is time to press Release. Wait about 45 minutes – that’s how long it takes it to rise to the surface – spot it on the surface, steam toward it, and get it onboard!

Quakey was the name proposed by Pobalscoil Iosolde, Palmerstown, Dublin 20 (teacher: Ms. Aileen Carthy, chemistry).

Quakey was the name proposed by Pobalscoil Iosolde, Palmerstown, Dublin 20 (teacher: Ms. Aileen Carthy, chemistry).

Good to see you back up, Quakey!

Sergei Lebedev, 27/04/2020

Day 3: Can you spot the OBS?

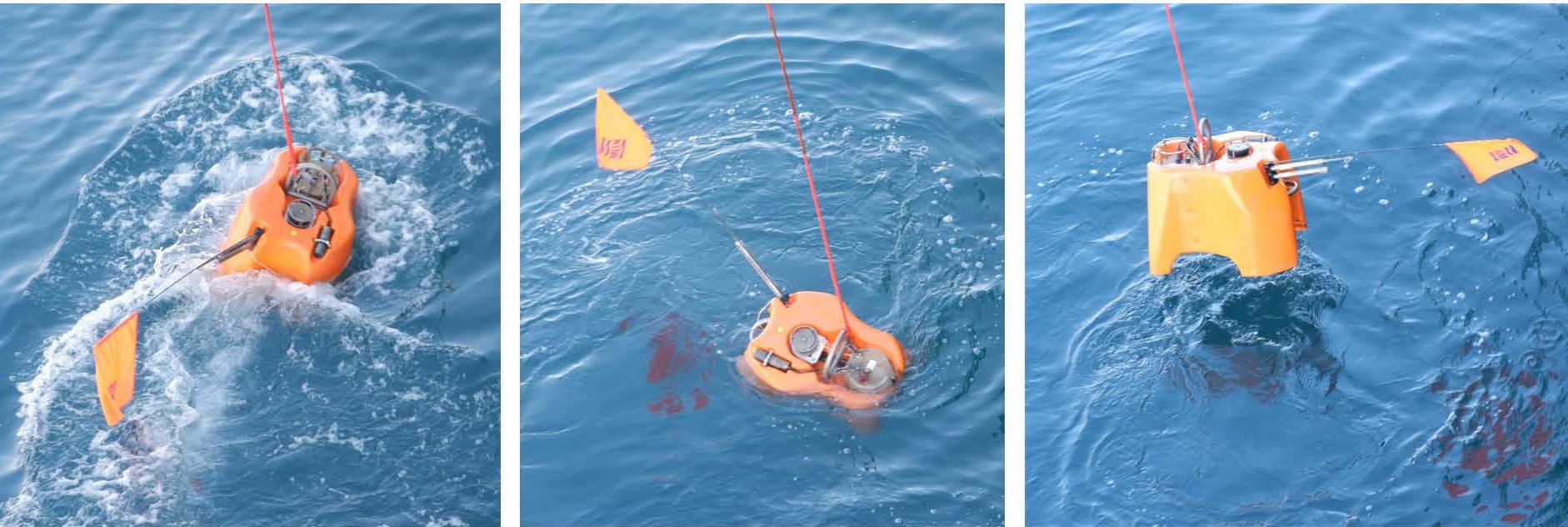

Something to celebrate – we have recovered the first of our 18 Ocean-Bottom Seismometers (OBS) from the seafloor this morning!

How does this work? Well. When we deployed the instruments, they had a steel anchor attached to them. With the weight of the anchor, they are heavy enough to sink – slowly – to the bottom of the ocean. Now that we want to recover them, we arrive with our ship to the exact location where an instrument was deployed, put a transducer (a device that emits acoustic signals at a frequency we specify) into the water overboard and send a signal to the instrument.

A very important part of the OBS is its acoustic release mechanism, which can hear the acoustic signals. Once it receives the command to release, it detaches the entire instrument from the anchor, and at this point the OBS becomes buoyant and rises – slowly – to the surface.

The next challenge is to spot the OBS at the ocean surface from the ship. Ocean currents tend to move the instruments by a few hundred meters away from the location they were dropped originally. It can be anywhere around the ship, and the retrieval may be taking place in the middle of the night or in rough weather. To make sure we can locate them, the instruments have a bright orange flag on a 1.3 metre long pole, a flashing-light beacon for night-time retrievals and a radio beacon.

Today, our retrieval was on a beautiful sunny morning, and two of us spotted the orange flag about 200-300 metres away from the ship. The ship then came next to the floating instrument, and it was hooked and lifted onto the deck.

Job done? Not quite. The first thing to worry about is getting the OBS back up to the surface and onboard. Once that is sorted, the next question is: has it recorded any data? Our data should be on the 256 GB, waterproof memory stick. Disconnecting that from the OBS and plugging it into a special data management device we see 168 GB of data on it – success!

The nominal lifespan of the battery in our seismometers was 14.5 months, but this one has recorded data from 22 September, 2018, to 1 March, 2020 – more than 17 months. Now it is time to copy the contents of the memory stick to hard drives and then – finally take a look at the data!

For now, just one more thing: our underwater seismic stations all have cool proper names, given to them by school students across Ireland and as far as in Italy:

The seismometer we got back today is Gráinne – after Gráinne Ni Mhaille (Grace O’Malley) (c. 1530 – c. 1603) – the “Pirate Queen,†the lord of the Ó Máille dynasty in the west of Ireland. It was named by the Our lady of Mercy Secondary School, Waterford, Co Waterford (teacher: Patricia Dunphy, geography).

Welcome back, Gráinne!

Sergei Lebedev & Ee Liang Chua, 27/04/2020

Day 2: Almost ready!

Sleeping at sea takes some acclimatisation, the boat is in constant motion, the waves never stop. The first night at sea was rough for some of us; trouble falling asleep, or waking up constantly. Your body needs to relax while your bed is in constant motion.

Fun fact: Seagulls and gannets sleep on open water when they are too far from shore to fly back to land!

Luckily the weather calmed and we woke up to the gentle rocking of the waves and through the ports we saw the sea welcoming us.

We are in the middle of the North Atlantic! Let the day begin.

The essential tasks of today were the preparation of the equipment for the retrievals. Installing the GPS antenna, preparing the instruments, setting up the labs.

The RV Celtic Explorer has two labs: the dry lab and the wet lab. The wet lab is where the OBS will be disassembled, the dry lab is where the data will be processed. In short: the wet lab is where the manual labour is carried out and in the dry lab where the computational power takes over.

For most of us it is the first OBS retrieval, thus we did a dry run through the full procedure of the recovery to make sure we are as prepared as we can be. The day passed by quickly and before we knew it dinner was ready and we were rewarded with excellent food and Black Forest cake. Now the evening has come and we are all set up for the challenges of tomorrow!

And now you are in for a treat: a crow’s nest view of our departure!

Janneke de Laat, Maria Tsekhmistrenko and Ee Liang Chua, 26.04.2020

*****

Day 1: The SEA-SEIS expeditions begins!

The air in our hair, the fresh breeze in our noses, the bright sun on our skin, the sea salt on our lips. We are finally back in the North Atlantic offshore Ireland and sailing towards the first OBS stations.

After 19 months of deployment, 18 OBS are awaiting to be recovered by 6 DIAS scientists.

Check out this liveblog of our deployment cruise in September 2018 if you want to know more about the the beginning of this science adventure.

In short: The ocean-bottom seismometers (or OBS) are sophisticated instruments that operate on the sea floor and record seismic data. Now that the battery of the OBS has reached the end of its lifespan it is time to bring them back home.

Over the next three weeks, we will tell you more about the expedition, the recovery process, the project, as well as life on board the RV Celtic Explorer.

Join the adventure!

Maria Tsekhmistrenko & Ee Liang Chua, 25.04.2020